Novo Nordisk Cities Changing Diabetes

Summary

As chronic diseases become more and more common, and stretch health systems beyond capacity, Novo Nordisk made a bold move: instead of trying to tackle conditions like type 2 diabetes through medication alone, it invested in something less expected: it worked with cities to change the conditions that shape health in the first place.

Over the last decade, Novo Nordisk’s Cities Changing Diabetes (CCD) programme (now expanded to Cities for Better Health (CBH) brought together over 300 organisations across 51 cities to shift how chronic disease is understood, prevented, and managed. It demonstrated that multi-sector collaboration is not just possible, but necessary to tackle chronic diseases, and drive better health outcomes in a sustainable way.

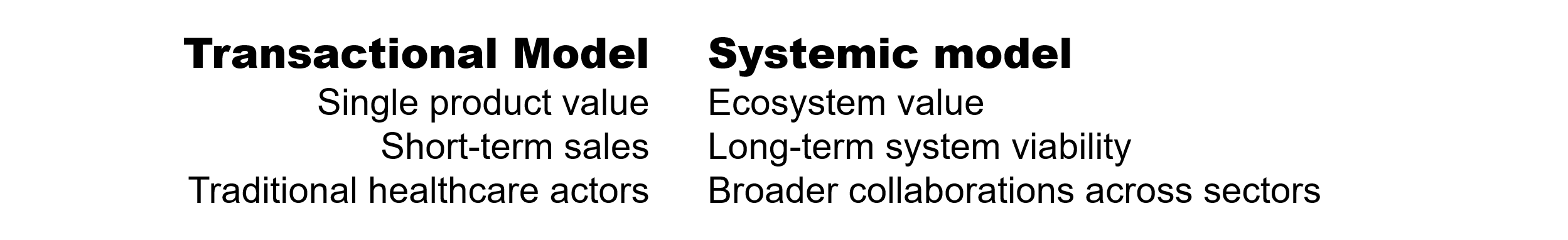

This programme is not a side-CSR project, nor is it a commercial activity. It is a conscious and strategic move from a purely transactional model, where the value proposition is a single product, to a systemic one, where the value is also in improving the overall health ecosystems. And while CCD/CBH is operationally separate from Novo Nordisk’s core pharmaceutical business, it directly reinforces the health systems that ultimately use and benefit from Novo Nordisk’s therapies.

This type of strategic shift could be a signal of what's to come. As chronic diseases continue to strain healthcare systems worldwide, more pharmaceutical companies will be forced to rethink their role in healthcare. Those who can deliver broader, long-term impact will have a distinct advantage.

This case study outlines what Novo Nordisk did differently, how it broadened the value it offers its stakeholders, and what others can learn from their playbook.

t

1. The Why

Novo Nordisk, already established in the chronic diseases therapy areas, recognised a critical, systemic risk: the continuous rise of chronic diseases like diabetes, cancer, and cardiovascular disease was driving unsustainable healthcare costs. This mounting pressure threatens the long-term viability of the very healthcare systems that purchase pharmaceutical products.

By initiating CCD, the company acknowledged that its core business of developing medicines was "insufficient" to solve this global problem. The programme was designed to invest in "health promotion and primary prevention", treating the structural causes of chronic disease in urban centres to stabilise health systems and "bend the curve" on disease prevalence.

This is an investment in ecosystem viability, positioning the company as a key partner and industry leader in structural health solutions, rather than just a product supplier.

2.The How: What Novo Nordisk did differently

The CCD operating model works as a self-reinforcing flywheel

Functional separation builds trust; trust enables cross-sector partnerships; partnerships generate deeper local insight; insight fuels shared learning and adaptation; learning helps cities embed health across systems (HiAP); and systemic action expands the definition of value, which in turn reinforces the value of the initiative for Novo Nordisk. Each turn strengthens the next. Each of these elements also amplifies the impact of CCD, and, in turn, draws on the programme’s insights, creating continuous two-way reinforcement between the initiative and its operating model.

1. Functional separation from commercial sales

The CCD programme was initiated and is governed directly by Novo Nordisk A/S, but implemented through a structure that is clearly distinct from the company’s commercial operations. The programme’s resources and activities focus exclusively on non-medical, upstream interventions.

The stated objective is to promote health and support primary prevention, leveraging multi-sector collaboration to address the conditions that determine whether people get sick, and who gets sick in the first place.

In practice, this meant collaborating with partners who are not traditionally involved in healthcare, but in urban design, transport, climate resilience and food systems. The ultimate goal is to stabilise and strengthen the broader health ecosystem, rather than drive short-term product sales.

The distinction from commercial activities is key, because it helps avoid conflicts of interest and reduces the risk of appearing to leverage public health challenges to promote commercial offerings. Importantly, the programme’s research and policy work is conducted under the guidance of independent academic institutions. This positions the programme as a credible policy actor rather than a commercial advocate, and opens the door to engaging high-level, non-health sectors of government and policy, audiences that do not typically interact with a pharmaceutical sales force.

2. Strategic partnerships

The CCD initiative began in 2014 with a founding trio of global partners and five cities. The founding partners were:

Novo Nordisk as initiator, sponsor and convenor.

University College London as a global academic lead, bringing rigorous, scientific research expertise in uncovering social and cultural drivers of diabetes.

Steno Diabetes Centre in Copenhagen bringing clinical and public health expertise to bridge research and healthcare delivery.

Together, this trio developed the core methodologies that would later guide the selection of local partners in each participating city.

As mentioned above, the objectives of the programme meant collaborating with some local partners who are not typically found in public health coalitions. For example, urban design firm Gehl Architects brought expertise in reshaping public space to promote everyday health, while the C40 Cities network introduced a climate-resilience lens that embedded health into broader sustainability agendas.

These partnerships signal a deliberate strategy to integrate health into how cities are built and governed, not just how they treat disease.

This is a core component of the program's systemic design and strategic value.

3. Data-driven methodology

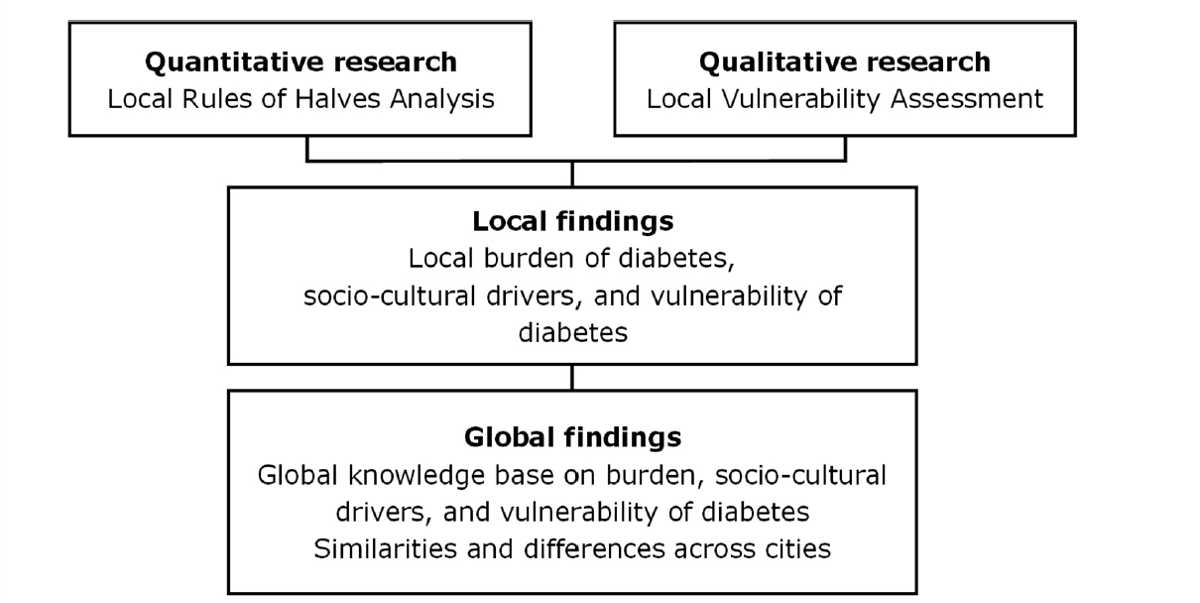

The programme started in 2014 with 5 participating cities. The first step in each city was to map the problem clearly and locally, using two tools:

1.The Rule of Halves

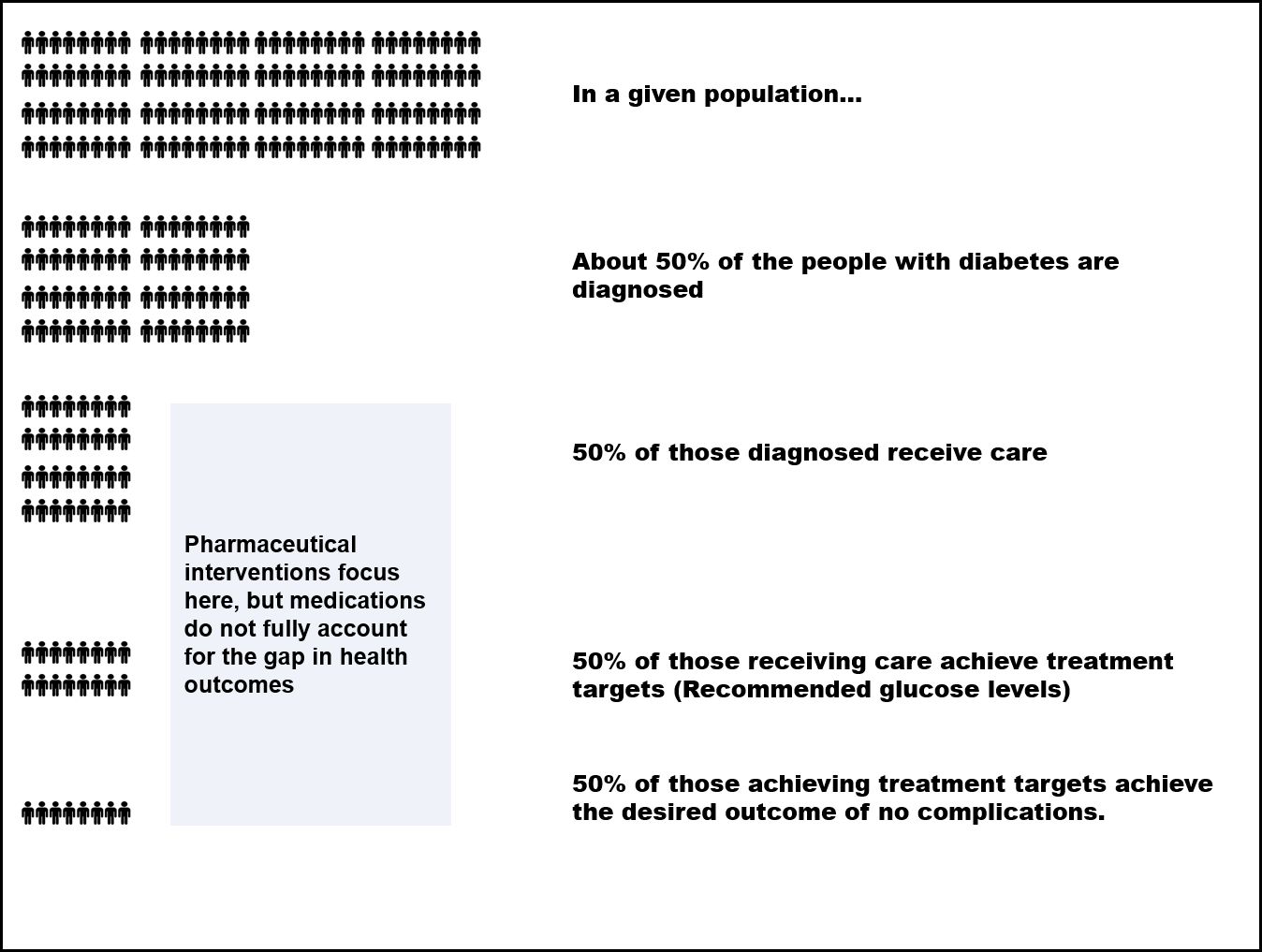

The Rule of Halves (RoH) is a theoretical framework used in various chronic diseases to measure levels of access to clinical care, adherence and effects of treatment. It addresses how diabetes care works in a specific population based on a simple hypothesis:

Half of the people with diabetes in a given population are not diagnosed

Half of those diagnosed are not receiving care

Half of those receiving care are not achieving treatment targets

Half of those achieving treatment targets are not achieving the desired outcome of no complications.

RoH serves to quantify gaps in diabetes care. Rather than starting with assumptions, each city starts with a local map of system failure and a clear entry point for systemic change.

The Rule of Halves Theoretical model is a quantitative measure of diabetes care in a given country. The pattern shown here is the starting hypothesis but varies from country to other. E.g. in Copenhagen, 74% are diagnosed and among those who are, 90% receive care, and out of those, 40%–60% have achieved target levels of treatment. Adapted from Napier et al. (2017)

Each city’s data was different. Some struggled with diagnosis, others with follow-up, others with treatment quality or access. This helped Novo Nordisk and its partners identify exactly where action was needed and who had the power to act.

Then they engaged those with the power to act in collaborative programmes, and empowered them with tools and resources to take appropriate action.

2. The Diabetes Vulnerability Assessment (DVA)

The second tool focused on why people were vulnerable in the first place. Through interviews, focus groups and ethnographic research, the DVA uncovered how cultural norms, stigma, work conditions, transport, religion and gender shaped people’s risk and their ability to access support.

Together, the RoH and DVA gave cities a clear picture of:

Where the system was failing

Who was being left out and why

What needed to shift and who needed to be involved

These insights became the foundation for action, not by Novo Nordisk, but by the cities themselves.

And while this initiative was completely separate from its commercial activities, it is clear that the rigorous research methodology applied locally, provides Novo Nordisk with granular intelligence on where healthcare systems are failing and why patients are falling out of care. This data is a competitive asset, offering deeper insights beyond traditional market research.

How this informs the company's future strategy, R&D, and market access models is unclear, but it would be surprising if this data was completely siloed within the CCD initiative.

4. Structures for learning and adaptation

The programme was designed as a dynamic feedback loop, transforming local insights into shared intelligence, and ultimately, to coordinated action, and then back round again as data and insights.

By facilitating the distribution of knowledge across the network, the programme enables participating cities to adapt to their contexts, resolve implementation challenges, and accelerate progress through collective learning. Examples of knowledge-sharing activities within the programme are:

Global knowledge exchange: Stakeholders engage through global summits, a series of webinars and regular newsletters that disseminate technical expertise and emerging best practices.

The UDAF Case Catalogue: As part of the Urban Diabetes Action Framework (UDAF), the Case Catalogue features documented interventions, and gives cities access to validated solutions that can be adapted to their lived realities.

5. Embedding health into the everyday functioning of cities: a health in all policies (HiAP) approach

The Cities Changing Diabetes programme adopts a Health in All Policies (HiAP) lens, recognising that health outcomes are not just shaped in clinics, but in the design, governance, and daily operations of a city. Instead of focusing on isolated, short-term interventions, the programme drives long-term, structural integration of health into policy, planning, and urban systems, positioning health as a shared responsibility across all sectors.

Policy integration at multiple levels

In China, the programme's insights contributed to the creation of a national Standard for Diabetes Health Management.

In Mérida, Mexico, in-depth community mapping and data analysis uncovered specific drivers of diabetes, such as lack of walkable infrastructure, limited access to nutritious food, and social isolation. This evidence was presented to city leaders and directly informed new municipal policies, such as urban zoning changes to support walkability, improvements in public health outreach, and targeted prevention programmes in high-risk neighbourhoods.

Reimagining urban environments for health

In Bogotá, the Healthy Neighbourhood Pilot turned abstract health goals into tangible changes on the street. Working with city planners and local communities, the programme redesigned public spaces to encourage healthy habits: They added street kitchens for healthier food access, invested in wider sidewalks for safe walking, and improved lighting and public safety to make outdoor spaces more inviting. As a result, people spent more time outdoors, ate more healthfully, and felt safer, proving that when cities are built for health, people live healthier lives.

Institutionalising cross-sector governance

In Italy, the programme helped catalyse the creation of the Health City Manager role: an institutional function embedded within municipal governments to ensure that health considerations are integrated across departments, from transport to education. This role was endorsed by The Italian Council of Ministers, and backed by funding, reflecting a permanent shift in health governance that goes beyond the traditional role of the department of health.

Together, these examples reflect a shift from treating health as a siloed issue to embedding it as a core function of city life. In this model, health is everyone’s business, woven into the decisions made by city planners, transport departments, faith leaders, and educators alike. This is Health in All Policies in action: building healthier cities not by treating illness, but by redesigning the systems that shape everyday life.

6. A broader definition of value

What makes Novo Nordisk’s approach notable is that they didn’t just measure the impact of their Cities Changing Diabetes programme. They also sought to understand the value it delivered to their partners.

Beyond improved health outcomes, partners consistently highlighted how the programme helped convene diverse stakeholders, build trust, and catalyse local ownership. For many, CCD became more than a corporate initiative, it became a platform that empowered them to act, access global expertise, and connect with like-minded cities facing similar challenges.

For pharma, this is a shift in the definition of value: Value is not only in molecules, but in enabling ecosystems that can deliver lasting health impact.

From pills to ecosystems

The next competitive edge isn’t just clinical efficacy, but also system efficacy. The CCD model proves that this can be done by a pharmaceutical company.

3. The Systems Thinking Playbook: Lessons for Pharma Leaders

The Cities Changing Diabetes model offers a practical roadmap for how pharmaceutical companies can move beyond product pipelines and become architects of resilient health systems. This is not about abandoning commercial interests, but about building the systems that ensure those interests remain viable in the long term.

1. Start with the System, Not the Symptom

Most healthcare strategies treat what the system produces (like diabetes), not why it keeps producing it. CCD shows that there is a great opportunity lies in redesigning the system itself. In this case, shaping cities so that health is the default outcome. That means engaging outside the traditional health sphere: in urban planning, education, food systems, and mobility.

Takeaway: Start mapping the upstream forces that create demand for your therapies, and explore where your influence can shift them.

2. Invest in Structural Change

Novo Nordisk empowered cities to change how they govern for health. From co-creating new municipal roles (like the Health City Manager) to embedding health goals in non-health actors (like C40 and Gehl), CCD shows how strategic investment can reshape institutions, not just fund short-term fixes.

Takeaway: Think beyond CSR. Use your resources to bring different stakeholders together, recode the rules so that health becomes part of how cities function, not just how they treat illness.

3. Influence Without Owning

CCD works because Novo Nordisk didn’t try to control the outcome. Instead, it acted as a neutral convener, building trust, credibility, and staying power. By creating a shared agenda across governments, NGOs, urban designers, and communities, the company positioned itself as a system integrator, not a vendor.

Takeaway: Influence comes from orchestration, not ownership.

4. Build Long-Term Market Viability

Chronic disease rates are rising. Public budgets are shrinking. Trust in pharma is fragile. The future doesn’t belong to the company with the best product, it belongs to the one with the most resilient market. CCD shows that by helping cities fix the conditions that produce disease, pharma companies can protect their relevance in an outcomes-based future.

Takeaway: Think of systems investment not as philanthropy, but as market infrastructure development.

The next competitive edge isn’t just clinical efficacy, but also system efficacy. The CCD model proves that pharma can play a legitimate, high-leverage role in system redesign. And that’s the bigger game: not winning in today’s market, but strengthening markets that can sustain innovation in the long term.

References

1. Cities Changing Diabetes - Programme review, accessed October 26, 2025, https://www.citiesforbetterhealth.com/content/dam/nnsites/cbh/en/knowledge-hub/reports/pdfs/cities-changing-diabetes-programme-review-2014-2023.pdf

2. Napier AD, Nolan JJ, Bagger M, et al. Study protocol for the Cities Changing Diabetes programme: a global mixed-methods approach. BMJ Open 2017;7:e015240. Accessed Novembre 3, 2025, doi:10.1136/ bmjopen-2016-015240

3. Holm AL, Andersen GS, Jørgensen ME, et al Is the Rule of Halves framework relevant for diabetes care in Copenhagen today? A register-based cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2018;8:e023211. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023211

4. Novo Nordisk - Oxford Academic, accessed October 26, 2025, https://academic.oup.com/book/39548/chapter/339411983/chapter-pdf/44100915/oso-9780198870708-chapter-33.pdf

5. ACTION ON URBAN DIABETES - Cities for Better Health, accessed October 26, 2025, https://www.citiesforbetterhealth.com/content/dam/nnsites/cbh/en/knowledge-hub/reports/pdfs/CCD_Briefing_Book_2021_UPDATE_Final.pdf

6. The Urban Diabetes Action Framework - Cities for Better Health, accessed October 26, 2025, https://www.citiesforbetterhealth.com/resources/tools/the-urban-diabetes-action-framework.html

7. Purpose and sustainability - Annual Report 2024 - Novo Nordisk, accessed October 26, 2025, https://annualreport.novonordisk.com/2024/strategic-aspirations/purpose-and-sustainability.html

8. Showcasing the value and impact of the Cities Changing Diabetes programme - Cities for Better Health, accessed October 26, 2025, https://www.citiesforbetterhealth.com/latest-news/cities-for-better-health-10-year-review-.html